The major historical and contemporary texts on children's drawing (Luquet, Piaget & Inhelder, Sully, Lowenfeld, Arnheim, Goodnow, Goodenough, Cox, Freeman, Costall, Golomb, and Fineberg) refer only to drawings which are representational, using conventional materials, dominantly pen or pencil, and sometimes paint on paper.

The examples I studied were almost all made with material that was already formed: they were chosen by the child, by no one else, from the countless possible things that were around them. They were made spontaneously without any demand or instruction from me or anyone else. This is of the utmost importance. I knew that they raised questions of fundamental importance about the nature of seeing itself. It was for these reasons that I decided to take it further.

EXAMPLES

'Skeleton' (R: 3.2)

This was done in another room and brought to me, completed, with the single word 'skeleton' stated as she gave it to me. First of all it was extraordinary to me that she was able to cut it out of an A4 sheet of copy paper in such a way that it held together; then the fact that it did indeed resemble a skeleton with a middle section that had rib-like shapes, then below it longer bits and pointed triangular parts which resembled legs and feet. Did she have an image in her mind beforehand, then make it? She was only three years old. Or did it occur to her during the process of cutting into the paper? Maybe it occurred to her afterwards when she held it up to bring it to me?

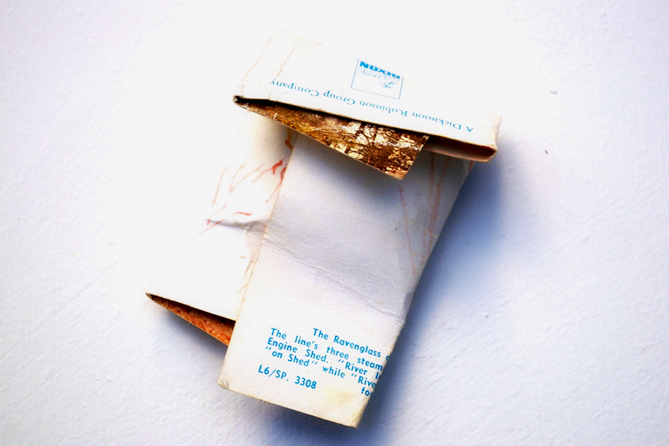

'Parcel' (J.3.6)

Why did she choose it? Her experience of being in the world at the time the postcard was bought was one of an only child enjoying the undivided attention of her parents. Was it possible that in bringing it to me in this form she was telling me something, reminding me of that time?

QUESTIONS

The images or objects they used were selected, and the fundamental question is, were they seen 'as' something in the moment in which they were seen, or did this kind of 'being seen' occur during the process of putting them together with something else, interacting with them, folding, cutting, drawing, etc?

How can we explain what the children did and what appears to us in the artefacts that they presented to me or to their father, without reference to the nature of their lives and their experience? However short the time of their experience, are we assuming that because a child is only three years old, she can have no knowledge of her life so far, and no understanding of it?

How did they see the things they used to make what they made so immediately, unless they saw them as something that could immediately become something they already saw in them?

what ifQUESTIONS

The images or objects the children used were selected. The fundamental question is, were they seen 'as' something in the moment in which they were seen, or did this kind of 'being seen' occur during the process of putting them together with something else, interacting with them, folding, cutting, drawing, etc?

WHAT CHILDREN MAKE OF THINGShow it began

Whilst looking after my daughters in their early years I watched with fascination as they transformed images and objects they found, manipulating and changing materials in ways both representational and abstract, using a very wide variety of media and methods. The examples I studied were almost all made with material that was already formed: they were chosen by the child, by no one else, from the countless possible things that were around them. They were made spontaneously without any demand or instruction from me or anyone else. This is of the utmost importance. I knew that they raised questions of fundamental importance about the nature of seeing itself.

'Skeleton' (R:3.2)

'Skeleton' (R:3.2)

... 'Parcel' (J:3.6)

... 'Parcel' (J:3.6)